The organisation of maternity care is paramount in providing safe, cost effective and normalised care for women (Sandall et al, 2010). Maternity care can be delivered using different models. These include midwife-led care—where a midwife is the lead professional but one or two consultations with an obstetrician or a physician is part of routine care; medical-led care—where an obstetrician or physician are the primary care providers; or shared care—where responsibility is shared among different health professionals.

Evidence for the safety and effectiveness of midwifery-led care has been available in various formats including primary research, reviews and guidelines (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2007; Hatem et al, 2008; Sandall et al, 2010; Sandall et al, 2013). In their Cochrane review, Sandall et al (2013) demonstrated explicit benefits for mothers and babies receiving midwifery-led care compared with other models of maternity care, with a comparable level of safety. The review included 13 trials, involving 16 242 women, from the UK, Australia, Canada, Ireland and New Zealand. Women receiving midwifery-led continuity models of care were less likely to experience regional analgesia, episiotomy and instrumental birth, and more likely to have a spontaneous vaginal birth, a known midwife attending the birth, no intrapartum analgesia and a longer mean length of labour. There were no differences between groups for caesarean births. Women who were randomised to midwifery-led continuity models of care were also less likely to experience preterm birth and fetal loss before 24 weeks’ gestation, although no differences in fetal loss and/or neonatal death after 24 weeks or overall were found. The majority of studies within the review also reported a higher rate of maternal satisfaction in the midwifery-led continuity care model. It is speculated that the main contributing factors to the observed differences lie in the philosophy of care behind each model (Soltani and Sandall, 2012). Midwifery-led care is based on the belief of normality in childbirth, continuity, advocating autonomy and building relationships with mothers, whereas in the medical model there may be an over-reliance on technology and preference for medical interventions. The Cochrane review (Sandall et al, 2013) concluded that the majority of women should be offered midwifery-led models of care, although caution should be applied with women with substantial medical or obstetric complications.

The results of this review, as well as its predecessor (Hatem et al, 2008), have had a significant impact in informing policy debate in the promotion of midwife-led care and facilitating decision making within the UK, Australia, the US and Brazil. However, despite showing that midwifery-led care is comparable with medically-led care in terms of safety outcomes (Sandall et al, 2009), little is known locally about the level of awareness and the extent to which maternity users utilise the evidence for midwife-led care. This is particularly important given that organisation of maternity care and facilitation of informed choice has been shown to be pivotal in enhancing women's experience of birth (Soltani and Sandall, 2012). Sandall et al (2013) only focused on midwife-led continuity models of care (rather than place of birth) and provided a narrative account of evidence in support of cost-effectiveness of this model. However, the cost benefits of all forms of midwifery-led care have been demonstrated in a UK-based study (Schroeder et al, 2012); with the unadjusted costs, at that time, of a planned homebirth—£1066, a standalone midwifery unit birth—£1435, an alongside midwifery unit birth—£1461 and an obstetric unit birth—£1631.

In view of the high national and international impact of the above evidence and the unknown extent of awareness of this and other midwifery-led care evidence among professionals and women, this survey was designed to explore local awareness of all forms of midwifery-led care evidence. This included evidence of care provided at home, in standalone birthing units and in alongside midwife units.

Objectives

The main objectives were to evaluate maternity users’ awareness of midwife-led care supporting evidence and the extent to which it influences their choices from both the mothers’ and practitioners’ perspectives.

Method

The project was carried out in a large teaching maternity unit in the Yorkshire and Humber region, where labour care is organised into midwifery-led care either at home or in an alongside midwifery unit or obstetric care in an obstetric unit. The alongside midwife-led unit shares an entrance with the consultant-led unit. All low-risk women are routinely referred to midwifery-led care and to give birth in the alongside midwifery-led unit.

The project was a service evaluation project. It took place in close collaboration with maternity users and practitioners. Approval for the project was obtained from the local service evaluation committee. Two surveys were developed: one aimed at professionals and the other at maternity service users.

Professionals’ survey

An online survey explored practising midwives and obstetric colleagues’ awareness of evidence regarding maternity care models with a focus on advantages and disadvantages of midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care. It contained both open and closed questions that explored what specific evidence professionals were aware of regarding midwife-led care, what evidence they had recently accessed, what evidence they would consider accessing in the future, and how they provided information to women to enable them to make choices about place of birth. The survey was piloted by four midwives and one medical colleague. Minor wording clarifications only were deemed necessary after piloting the survey.

All midwives and obstetricians working within the maternity unit were included in the sample. A link to the survey was emailed to all qualified staff asking them to participate with a reminder email sent 3 weeks later.

Maternity user's survey

The survey was developed involving user groups to evaluate women's knowledge of midwifery-led care, their knowledge of supporting evidence and the factors influencing their decision-making. The survey contained open and closed questions and was piloted with 6 user group representatives. Eligible women for the survey included those who were currently pregnant or those who had given birth from 2008 when the original Cochrane midwife-led care review was published. The survey was promoted by the community midwives and local maternity user groups, and advertised through local employers to eligible staff. The survey ran from September 2013 to February 2014. The survey was fully confidential and available in both paper format or online depending on women's preferences.

Data analysis

For both surveys descriptive statistics were calculated for all demographic data and for closed answer questions including proportions, means, standard deviation (SD) and ranges as appropriate. The demographic data was compared to unit or national means or proportions to determine the comparability of the sample to the population. Open-ended questions were analysed using thematic analysis to establish categories.

Results

Professionals’ survey

The characteristics of this sample are presented in Table 1. Fifty-nine health professionals completed the professionals’ survey, which gave a response rate of 15.1%. Forty-eight respondents were midwives, five were obstetricians and six did not complete this question. Midwives had been qualified for between 2 and 40 years and the obstetricians for between 3 and 34 years.

| Staff type | n (%) | Total population |

|---|---|---|

| Not stated | 6 (10.2%) | |

| Midwives | 48 (81.3%) | 345 (88.5%) |

| Years qualified [mean (range)] | 17.2 years (2–40 years) | |

| Band 5 | 2 (4.4%) | 39 (11.3%) |

| Band 6 | 29 (64.5%) | 259 (75.1%) |

| Band 7 | 10 (22.2%) | 41 (11.9%) |

| Band 8+ | 4 (8.9%) | 6 (1.7%) |

| Community-based | 16 (33.3%) | 92 (26.7%) |

| Hospital-based | 25 (52.1%) | 253 (73.3%) |

| Managerial/specialist | 7 (14.6%) | |

| Obstetricians | 5 (8.5%) | 45 (11.5%) |

| Years qualified [Mean (range)] | 15.7 years (3–34 years) | |

| Senior house officer | 1 (20.0%) | 14 (31.1%) |

| Registrar | 2 (40.0%) | 12 (26.7%) |

| Consultant | 2 (40.0%) | 19 (42.2%) |

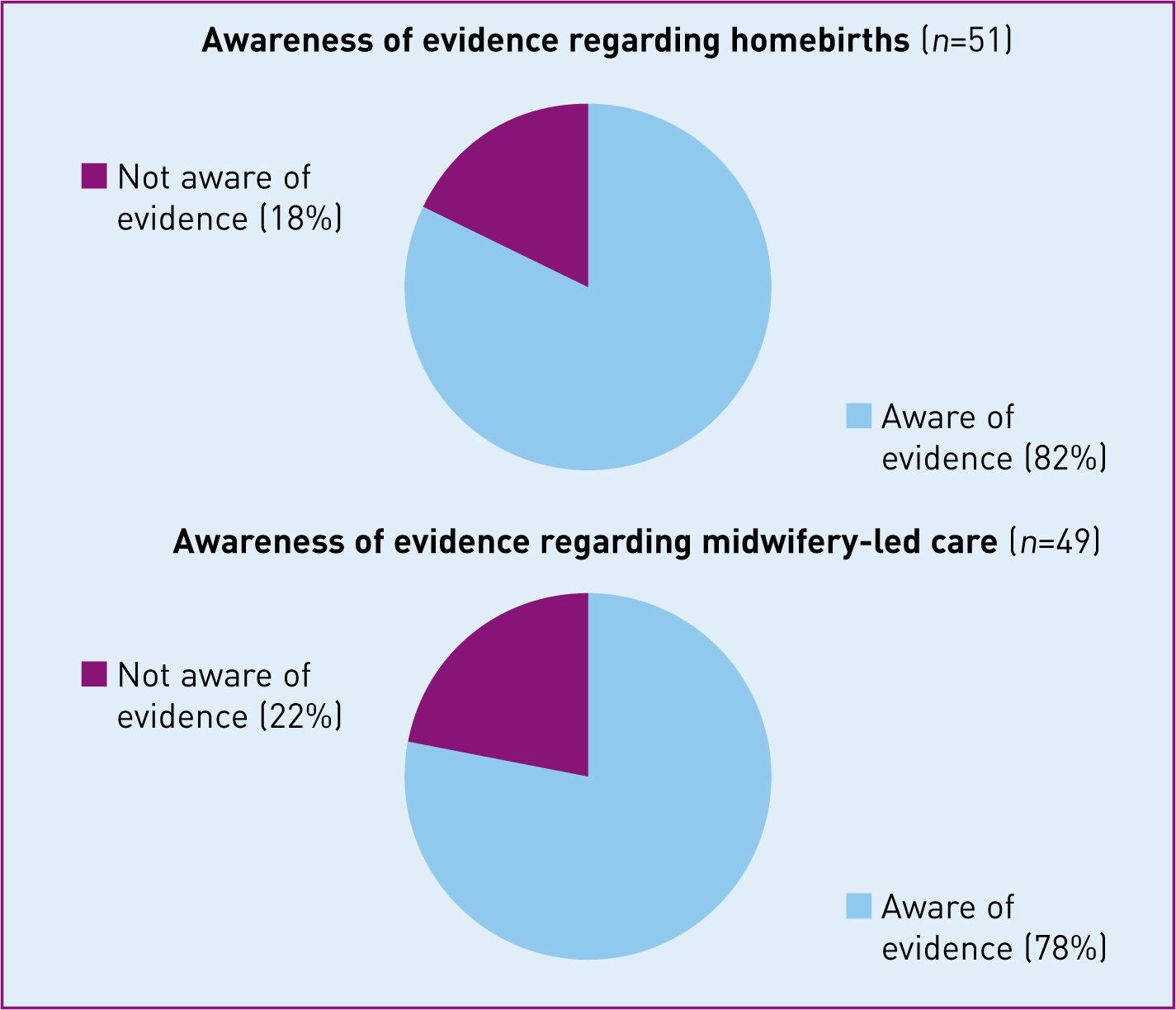

When asked about their awareness of evidence, 82% of professionals were aware of homebirth evidence and 78% aware of midwife-led care evidence (Figure 1). Professionals reported reading the Cochrane midwife-led care review less frequently (23.1%) than the NICE (2007) guidance (90.4%) or the local hospital guidance (88.2%) (Table 2).

| Local labour guidelines n (%) | National intrapatrum guidelines (NICE) n (%) | Cochrane midwife-led continuity models vs other models of care review n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 45 (88.2%) | 26 (50.0%) | 3 (5.8%) |

| Summary only | N/A | 21 (40.4%) | 9 (17.3%) |

| No | 5 (9.8%) | 3 (5.8%) | 35 (67.3%) |

| Don't know | 1 (2.0%) | 2 (3.8%) | 5 (9.6%) |

NICE—National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

When professionals were asked what evidence they had accessed for place of birth information in the last 6 months, the Cochrane library had been accessed less (19.0%) than other sources such as journals (64.3%) and national guidance (52.4%) (Table 3). Less than half of the professionals stated that they would use the Cochrane library if they wanted to find further pregnancy or birth information (Table 3).

| Evidence | Accessed in last 6 months for place of birth information n (%) | Would access in the future for pregnancy or birth information n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Journals | 27 (64.3%) | 7 (14.0%) |

| National guidance (NICE / RCOG / RCM) | 22 (52.4%) | 47 (94.0%) |

| Local policies and guidance | 18 (42.9%) | 39 (78.0%) |

| Internet | 18 (42.9%) | 3 (6.0%) |

| Conferences/study days | 14 (33.3%) | 2 (4.0%) |

| Cochrane library | 8 (19.0%) | 23 (46.0%) |

| Other | 3 (7.1%) | 2 (4.0%) |

NICE—National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; RCOG—Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; RCM—Royal College of Midwives

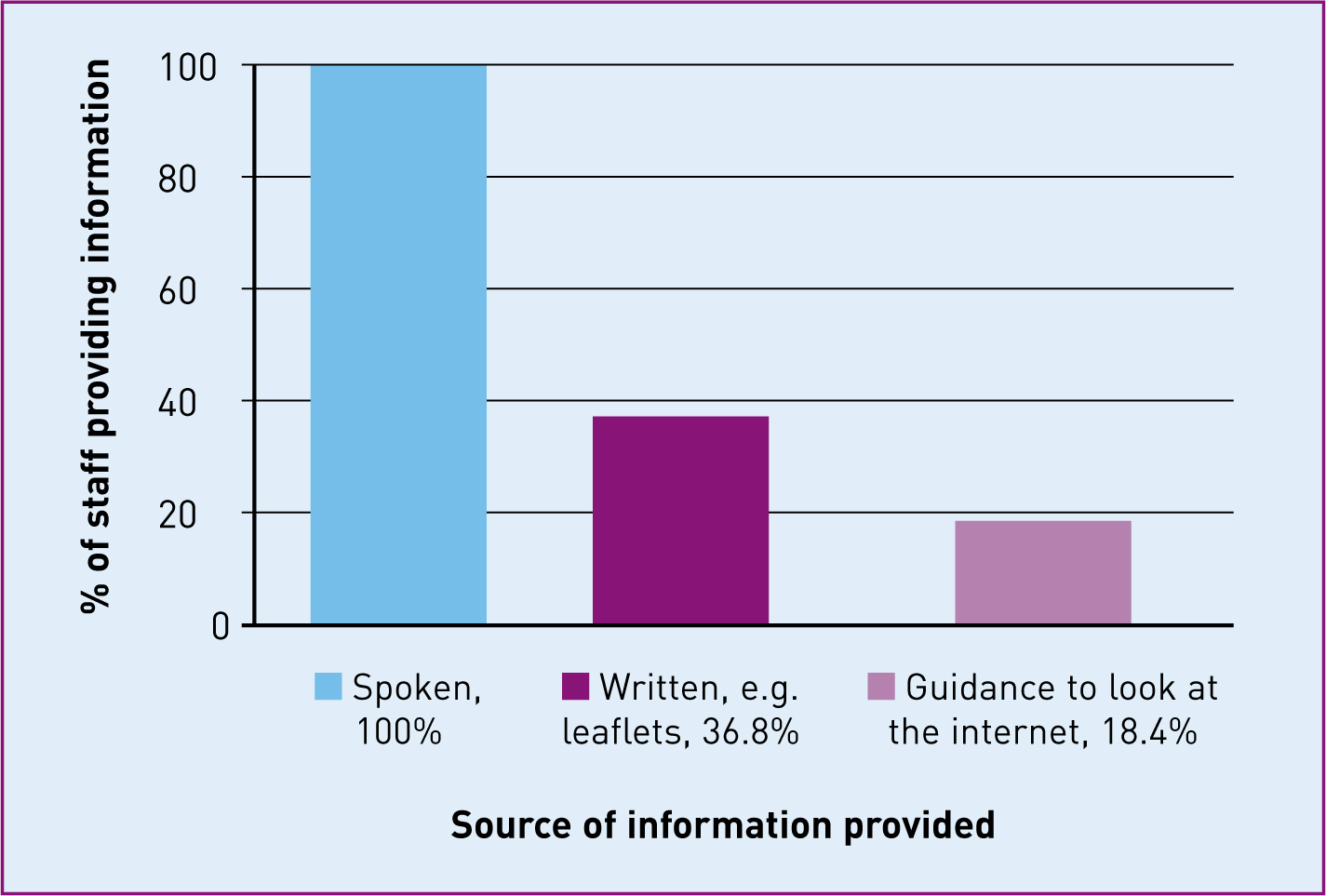

Of the 59 respondents, 39 directly provided women with information about place of birth, of which 100% provided verbal information, 36.8% written information such as leaflets and 18.4% guidance to look at specific internet sites (Figure 2).

Maternity user's survey

No-one requested a paper-based copy of the survey and 137 people clicked to take part in the online survey. The first question tested eligibility to participate. Nine did not meet the inclusion criteria and 11 women only responded to the eligibility question. A total of 117 women, therefore, completed, or partially completed, the survey and were included in the analysis. Of these women 48.7% (n=57) were antenatal and 51.3% (n=60) were postnatal (Table 4). The women participant's characteristics are presented in comparison to national data (Table 5). The women had an average age of 31.6 ± 4.8 years and 82.3% had received education beyond A-level.

| Weeks pregnant | Antenatal n (%) |

| less than 11+6 | 19 (33.3%) |

| 12–27+6 | 19 (33.3%) |

| 28–40+ | 15 (26.4%) |

| not stated | 4 (7.0%) |

| Year gave birth | Postnatal n (%) |

| 2008 | 3 (5.0%) |

| 2009 | 9 (15.0%) |

| 2010 | 10 (16.7%) |

| 2011 | 5 (8.3%) |

| 2012 | 21 (35.0%) |

| 2013 | 9 (15.0%) |

| 2014 | 1 (1.7%) |

| not stated | 2 (3.3%) |

| Antenatal n (%) | Postnatal n (%) | Combined n (%) | Nationally n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parity having/had: | ||||

| First baby | 20 (38.5%) | 32 (57.1%) | 52 (48.2%) | (40.4%)* |

| Second baby | 24 (46.2%) | 20 (35.7%) | 44 (40.7%) | (30.4%)* |

| Third baby | 6 (11.5%) | 3 (5.4%) | 9 (8.3%) | (15.0%)* |

| Fourth+ baby | 2 (3.8%) | 1 (1.8%) | 3 (2.8%) | (14.2%)* |

| Age | ||||

| <20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (4.6%)* |

| 20–24 | 5 (9.8%) | 4 (7.0%) | 9 (8.4%) | (18.2%)* |

| 25–29 | 11 (21.6%) | 13 (22. 8%) | 24 (22.2%) | (28.1%)* |

| 30–34 | 28 (54.9%) | 19 (33.3%) | 47 (43.5%) | (29.7%)* |

| 35–39 | 4 (7.8%) | 16 (28.1%) | 20 (18.5%) | (15.5%)* |

| 40+ | 3 (5.9%) | 5 (8.8%) | 8 (7.4%) | (3.9%)* |

| Average age (mean ± s.d) | 30.9 ± 4.5 | 32.2 ± 5.1 | 31.6 ± 4.8 | 29.8∞ |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White British | 89 (93.7%) | (79.8%)Đ | ||

| Other | 6 (6.3%) | (22.2%)Đ | ||

| Language | ||||

| English first language | 93 (97.9%) | (92.0%)Đ | ||

| Non-English | 2 (2.1%) | (8.0%)Đ | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/living with partner/civil partner | 94 (98.9%) | (78%)† | ||

| Living alone | 1 (1.1%) | (22%)† | ||

| Living with family adults | 0 | – | ||

| Living with unrelated adults | 0 | – | ||

| Education level | ||||

| No qualification | 0 | (22.5%)Đ | ||

| GCSE/O-level/NVQ 2 | 8 (8.3%) | (28.5%)Đ | ||

| ONC/BTEC | 3 (3.1%) | |||

| A-level/Highers/Bac/NVQ 3 | 6 (6.3%) | (12.4%)Đ | ||

| NVQ 4/Diploma | 8 (8.3%) | (27.4%)Đ | ||

| Degree/NVQ 5 | 35 (36.5%) | |||

| Postgraduate | 36 (37.5%) | |||

| Other | 0 (0%) | (9.3%)Đ |

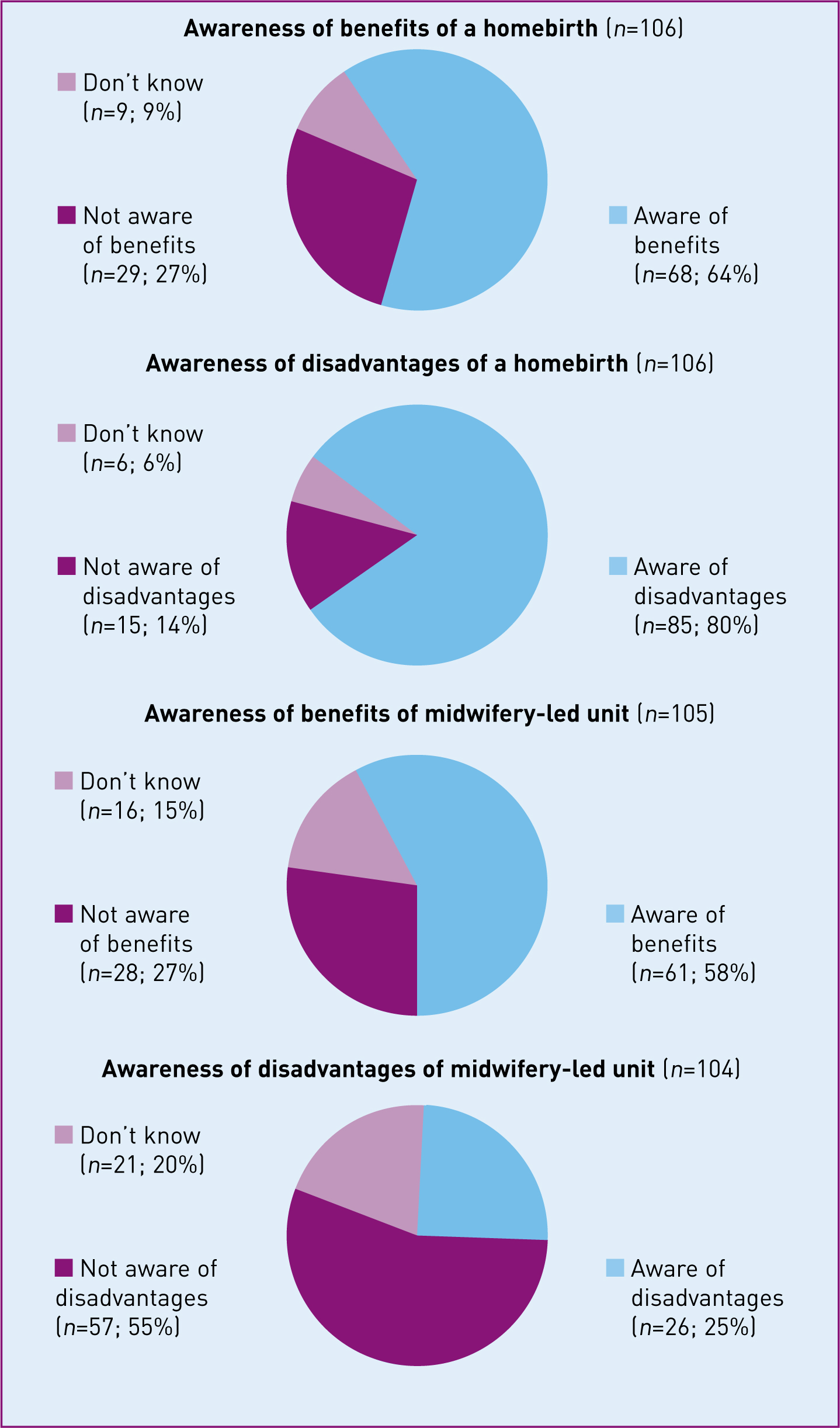

To explore women's awareness of supporting evidence, they were asked whether they were aware of any benefits and disadvantages firstly of a homebirth and secondly of a birth in a midwife-led care unit. Overall, 64% of women were aware of benefits of having a homebirth compared to 80% aware of disadvantages (Figure 3). The most common benefits women described were that a homebirth is more calm and relaxed (n=35; 55.6%), there is less unnecessary medical intervention (n=25; 39.7%), it is a more familiar environment (n=20; 31.7%), it is more comfortable than hospital (n=16; 25.4%), it provides more consistent midwife care (n=15; 23.8%) and it allows partner's to be more involved during the birth and postnatal period (n=12; 19.0%). Women viewed the biggest disadvantage of a homebirth to be that medical assistance is not available should it be required (n=57; 72.2%). Other perceived disadvantages were the time it would take to transfer to hospital should an emergency occur (n=27; 34.2%) and that no epidurals are available at home (n=24; 30.4%). Women who had considered a homebirth but had subsequently changed their mind were asked what factors had influenced their decisions. The most common reasons cited by these 27 women for changing their mind were the perception that they would be safer in hospital (n=12; 44.4%), medical advice due to their changing risk status during pregnancy (n=7; 25.9%), receiving insufficient or inaccurate information (n=3; 11.1%) and the concerns of their partner (n=3; 11.1%).

For birth in a midwife-led unit, 58% of women were aware of benefits compared to 25% aware of disadvantages (Figure 3). The most commonly identified benefits of a midwifey-led unit birth were the focus on normality and/or the use of fewer medical interventions (n=30; 56.6%), the more ‘homely’, less clinical atmosphere (n=16; 30.2%), the relaxed, calm atmosphere (n=15; 28.3%), the proximity of medical facilities if required (n=12; 22.6%) and women perceiving they had more control over their birth than in an obstetric unit (n=10; 18.9%). Women believed the main disadvantages of a midwifery-led care unit birth to be possible delays in accessing emergency care from standalone units (n=10; 41.7%), the need to transfer to consultant care if complications arise (n=9; 37.5%) and the lack of epidural facilities (n=8, 33.3%). Overall 87.7% (93/106) of women could name an advantage, disadvantage or both for having a homebirth, but only 61.0% (64/105) of women could do the same for a midwifery-led unit birth.

Just over 23% of women were aware of the NICE (2007) intrapartum guidelines, and 7.7% of the Cochrane midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care review. In both instances, 75% of the women that were aware had read all/part of them (Table 6). Of those who had read the NICE (2007) intrapartum guideline 88% found them helpful, but almost 30% found the guidelines difficult to read. All six women who had read the Cochrane review stated that they found it helpful and easy to read.

| Antenatal and postnatal combined n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Heard of NICE (n=104) | |

| Yes | 80 (76.9%) |

| No | 24 (23.1%) |

| Don't know | 0 |

| Heard of NICE Intrapartum Guidelines (n=104) | |

| Yes | 24 (23.1%) |

| No | 76 (73.1%) |

| Don't know | 4 (3.8%) |

| Read NICE Intrapartum Guidelines (n=24) | |

| No | 6 (25.0%) |

| Yes, summary | 9 (37.5%) |

| Yes, full guideline | 9 (37.5%) |

| Heard of Cochrane Library (n=103) | |

| Yes | 22 (21.4%) |

| No | 81 (78.6%) |

| Don't know | 0 |

| Heard of Cochrane ‘Midwife-Led continuity versus other models of care’ review (n=103) | |

| Yes | 8 (7.7%) |

| No | 94 (91.3%) |

| Don't know | 1 (1.0%) |

| Read Cochrane ‘Midwife-Led continuity versus other models of care’ review (n=8) | |

| No | 2 (25.0%) |

| Yes, abstract | 1 (12.5%) |

| Yes, lay summary | 3 (37.5%) |

| Yes, full review | 2 (25.0%) |

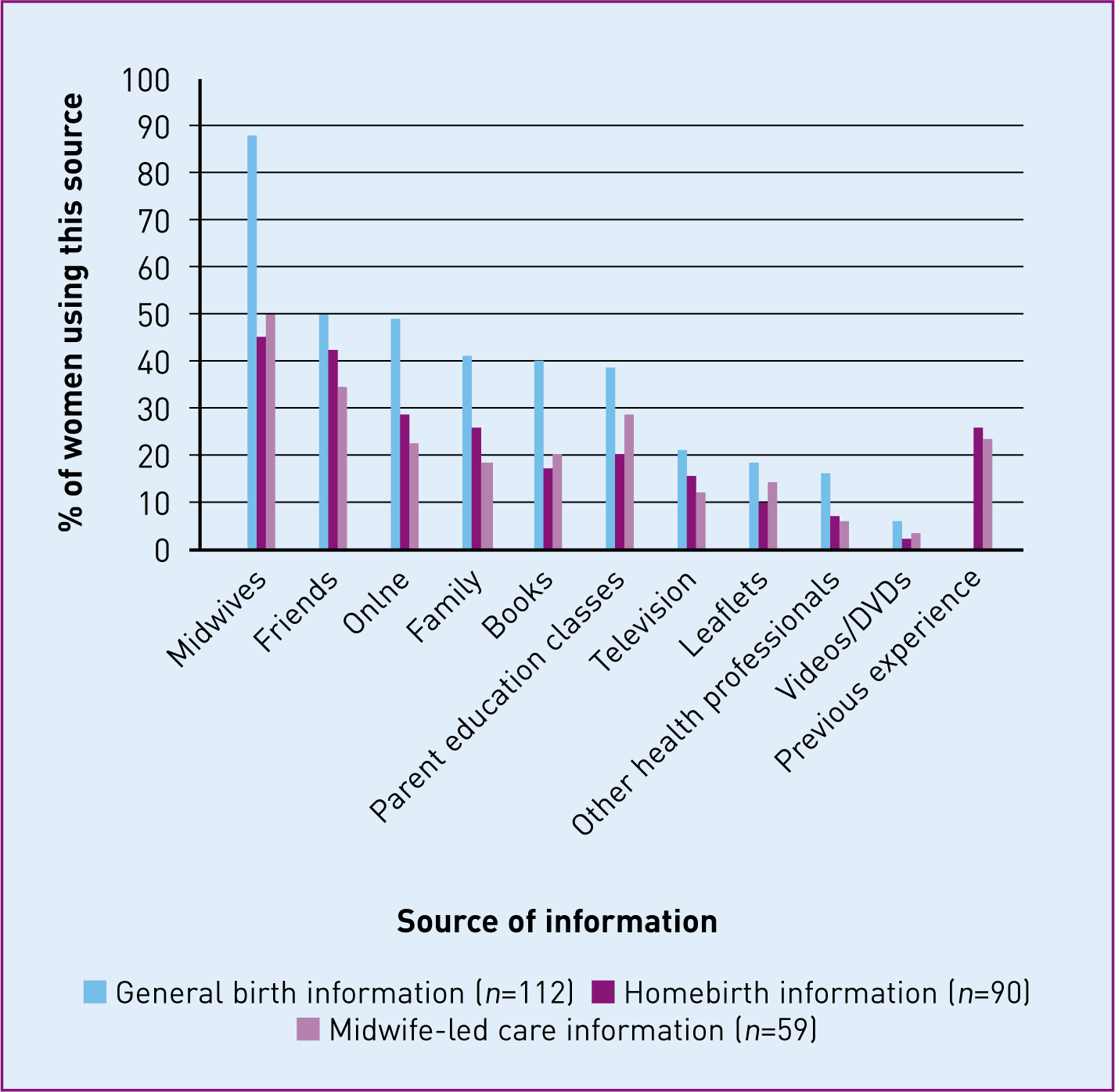

Figure 4 shows where women obtained general birth information and where they specifically obtained information about homebirth and midwifery-led units. For general birth information a large proportion of women (87.5%) relied on midwives. Midwives were also the main source of information about midwifery-led care and homebirths (49.2 and 45.6%, respectively). For all forms of birth information friends were the next most common source of evidence. Other common sources of birth information included the internet, antenatal education classes, family members and books. When it came to women's awareness of homebirth or midwife-led units, women's previous birth experiences were also important.

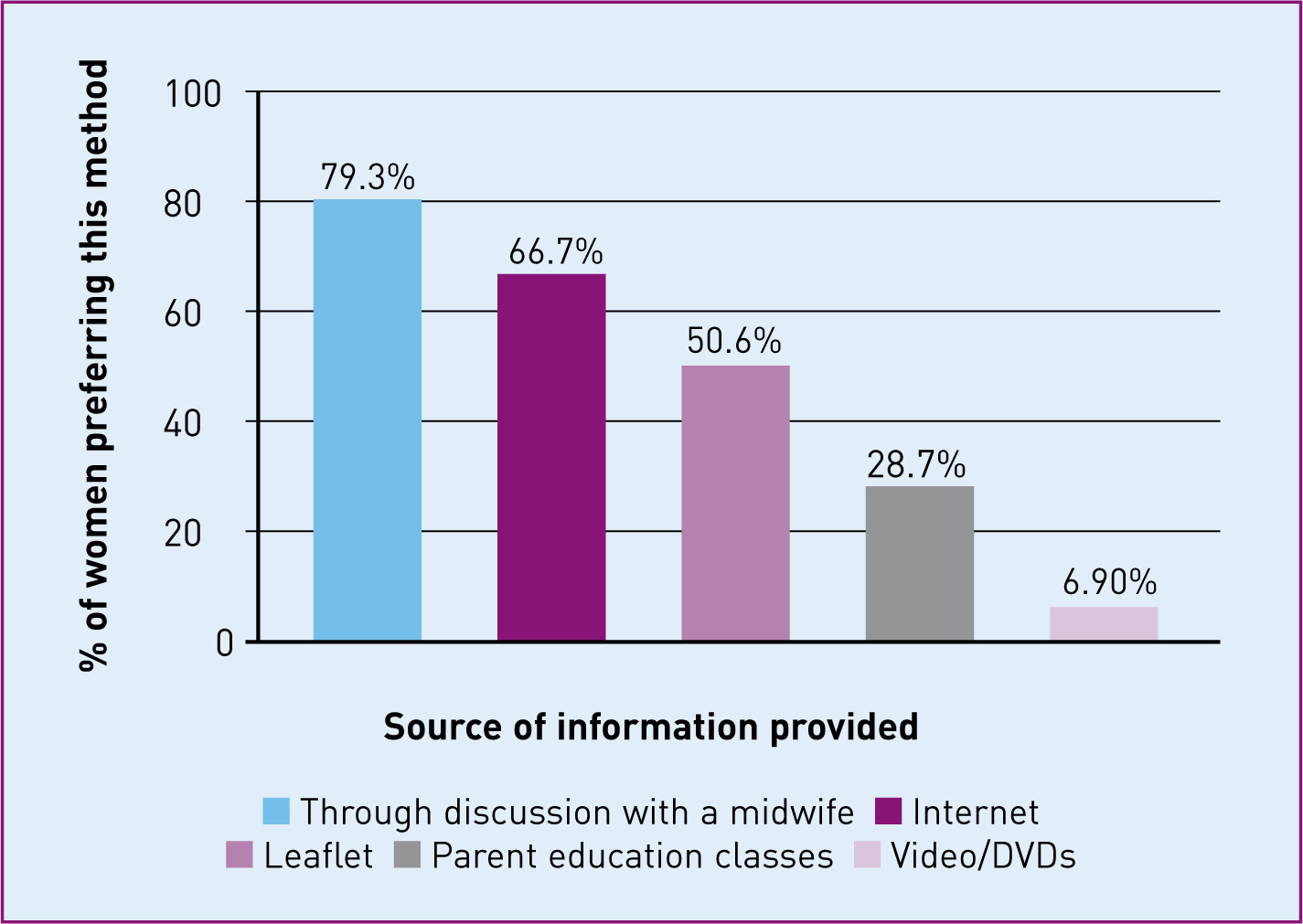

Finally women were asked how they would like to receive information about place of birth (Figure 5). The majority of women (79.3%) wanted discussion with a midwife to be the primary source of birth information, with the internet closely following this (66.7%). A separate question using a Likert scale verified this with 74.2% of women agreeing or strongly agreeing that the internet was a good way to receive information about place of birth options.

Discussion

This study examined awareness of evidence regarding different maternity care models and service provision, from both women's and professionals’ perspectives. Although it may not be representative of all maternity care provision due to the study being conducted at one maternity unit and having a small sample size, it provides insights into evidence awareness.

The response rate for the professionals’ survey was 15.1%. While this is low, it is above the response rates of 11.9% (Antheunis et al, 2013) and 4% (Howard et al, 2013) for previous surveys emailed to health professionals. The time pressures on staff in the current NHS climate could have negatively influenced the response rate. Those that did respond were fairly representative of the population, with all grades of staff represented for midwives and obstetricians and with a similar distribution between community and hospital midwives to the actual population.

While the majority of health professionals had read the national NICE guidelines, and the local Trust guidelines, only 5.8% had read the Cochrane review (Hatem et al, 2008). The survey found only 19% of health professionals had accessed the Cochrane library to obtain information on place of birth in the last 6 months and 46% of professionals stated they would use the Cochrane library to find pregnancy or birth evidence in the future. This is an important observation since Cochrane is considered the gold standard in the era of evidence-based practice, due to their rigorous and systematic approach aimed at supporting health professionals in their clinical decision making (Bero and Rennie, 1995). This study raises questions as to how well this resource is used among professionals; despite its awareness and use being important for clinical practice. This study found that women favoured midwives as their primary source of birth information; therefore, midwives need to have up-to-date knowledge and be familiar with the latest evidence, including Cochrane reviews. Professionals’ access to the Cochrane library therefore needs to be made a priority.

Antenatal women who participated in the survey were fairly evenly distributed across the different trimesters (Table 4). For most postnatal women their experiences of maternity care were very recent, with 51.7% having given birth since 2012, which should have minimised the risk of recall bias. Evidence has shown that women's long-term recall of many pregnancy and birth factors are accurate (Simkin, 1992; Tomeo et al, 1999). The sample had a higher rate of women having their first baby (48.2%) or second baby (40.7%) than the national average (40.4% nationally having a first baby and 30.4% a second baby). The average age of the women in this study was slightly higher than the national average for all women giving birth (31.6 vs 29.8 years). Although the proportion of women for whom English was their first language was higher in this study than the national average (97.9 vs 92.0%); when compared to the Yorkshire and Humber average of 94% (Office for National Statistics (ONS), 2011) it was slightly more representative. The sample was highly educated with 82.3% having some form of education after A-levels. Other studies of how women obtain pregnancy information had similar educational demographics, ranging from 62–76% of participants having tertiary education (Larsson, 2009; Gao et al, 2013). The internet-based nature of the women's survey meant it was not possible to record the number or characteristics of non-responders to determine if they differed in any way from those that did respond.

Women within the sample were more aware of evidence about homebirth than midwife-led care, with almost 40% unaware of any benefits or disadvantages of midwifey-led care. Similarly to previous research (Zadoroznyj, 2000) many women obtained information about midwifey-led care and homebirth from their previous birth experiences. Women also had a low level of awareness of specific evidence, with just 23.1% knowing about the NICE (2007) intrapartum guidelines and 7.7% about the Cochrane midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care review. Furthermore, 30% of those who had tried to read any of the NICE (2007) guidelines had found them difficult to understand, despite all of these respondents having some form of tertiary education. In comparison, all of those who had read the Cochrane review had found it easy to understand. In the UK, access to the online Cochrane library is free; with Cochrane providing evidence in different formats including podcasts to ensure a wider access. Cochrane reviews specifically incorporate lay summaries with the intention of making the review more accessible and understandable to the lay population. However, the lack of awareness and use of this resource among both the professional sample and the sample of women highlights the importance of the visibility of this resource to the non-academic population. Research is needed to establish the reasons for the limited awareness and use of the Cochrane library. Once identified these reasons can be addressed accordingly through forums or targeted campaigns to raise awareness and engage a wider audience both among health care users and health professionals.

Women's autonomy of choice of place of birth has been repeatedly promoted (Department of Health, 1993; NICE, 2007) and has been recently re-emphasised in the new NICE intrapartum care guidance (NICE, 2014). However, a large proportion of women viewed hospital as safer, with 80% of women stating they were aware of a disadvantage of having a homebirth and 44% of those who decided against a homebirth did so for safety reasons. This is in line with the findings of Lavender and Chapple (2005), who found that women decided against a homebirth due to the perceived safety of hospital. The over-medicalisation of birth and the perception of childbirth as a dangerous event may have contributed to women having a lack faith in their ability to give birth, which causes them to become over-reliant on hospital safety and to be dominated by the ‘just in case’ when making decisions about place of birth (Zadoroznyj, 2000; Houghton et al, 2008; Pitchforth et al, 2009). There is evidence that health professionals similarly see hospital as the safest place for birth (Houghton et al, 2008). Women's views may mirror health professionals’ views on the safety of hospital over the home setting (Lavender and Chapple, 2005; Houghton et al, 2008). In this study, some women decided against a homebirth after being provided with inaccurate or insufficient information. The limited information provided about homebirth could also be due to professionals’ assumption that women will bring up the conversation about place of birth if they are interested, while women themselves find it difficult to bring up the subject with a midwife (Houghton et al, 2008). Professionals therefore need to provide all women with accurate and detailed information about all care options including midwifery-led care and homebirth, to allow women to make a truly informed decision about place of birth.

When comparing this survey to a similar one carried out in 2005 in a maternity unit in Derby (Soltani and Dickinson, 2005), it was found that health professionals remained the most important source of information during pregnancy, with 88% of women in both samples obtaining information from health professionals. Friends were the second most important source of all birth information. However when combined with family, over time they had become a less used source, falling from 72–62%. In contrast, the use of the internet to obtain information had almost doubled—from 28% of women using the internet to 50% of women. Although the survey was offered in a paper format, all responses were from the online version. Caution is therefore required when interpreting the fact that women wanted increased web-based resources, as mainly technology-literate women will have been recruited. However, the phenomenon of women using the internet to obtain pregnancy and birth information is being seen globally (Larsson, 2009; Gao et al, 2013).

Women's desire to obtain pregnancy- and birth-related information over the internet (66.7%) differed markedly with how health professionals were currently providing information (18.4%). This may partly be due to 90% of midwives being concerned about the accuracy of the information that women can access online (Lagan et al, 2011). However, given the competing demands on midwives’ time, the internet can provide information to women that complements midwife contact. Information provision should not exclusively be online because internet use is not universal and direct contact with health professionals is still a top priority for women. However, because 83% of households in the UK now have internet access and 97% of females aged from 16–44 are reported to have used the internet in the last 3 months (ONS, 2013b), supplementary internet resources integrated with midwife consultation must be considered for women. With appropriate training health professionals can then confidently guide women to high quality, trustworthy, user-friendly web-based resources to ensure effective access to accurate information.

Conclusions

Despite good use of local and NICE guidance by professionals, the Cochrane library was underused. The majority of women were also unaware of this resource. Research needs to establish ways to promote this resource and current reasons for underutilisation.

There was a lack of awareness of evidence among the women. The most favoured way for women to receive information was from a midwife; therefore, there is a clear need for increased evidence provision about the birth options available and the research evidence supporting these options from professionals to women.

Women's desire for pregnancy and birth information to be provided online was demonstrated, with women widely using the internet during pregnancy and perceiving it as a good way to receive information. Internet options incorporating the available evidence need to be established that are reliable and easily accessible to women, to enable women to have sufficient information to make informed choices.